THE PLASTIC STUDIO

Chamber Music Festival

CLIENT

Chamber Music Festival

SERVICES

Artistic Direction

3D Animation

Graphic Design

The 8th Chamber Music Festival is inspired by the great El Greco. The Cretan Doménikos Theotokópoulos, widely known as El Greco (“The Greek”) boasted a dramatic and expressionistic style, which was met with puzzlement by his contemporaries but found appreciation in the 20th century. El Greco has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual, that he belongs to no conventional school.

Three musical works from Jon Leifs, George Tsontakis and Philippos Tsalahouris carry into the 20th and 21st century El Greco’s intense spiritual force. Similar to the painter’s life, the 2019 Chamber Music Festival Chania embarked on a musical journey through Greece, Italy and Spain, exposing musically the same unique “colours” of each country, that shaped the painter’s visionary art.

Born in 1541, in either the village of Fodele or Candia (the Venetian name of Chandax, present day Heraklion) on Crete, Dominikos Theotokopoulos was descended from a prosperous urban family. Here El Greco received his initial training as an icon painter of the Cretan school. Tempera and gold on wooden panels, post-Byzantine and Italian mannerist stylistic and iconographic elements where characteristic of his early art.

Candia was a center for artistic activity where Eastern and Western cultures co-existed harmoniously, where around two hundred painters were active during the 16th century. Crete and Greece were through the history meeting points, fertile soils for fresh ideas coming from the west and the east. This environment proved indispensable for the birth of a civilisation so unique in its intellectual produce as El Greco’s art itself.

It was natural for the young El Greco to pursue his career in Venice, Crete having been a possession of the Republic of Venice since 1211. Though the exact year is not clear, most scholars agree that El Greco went to Venice around 1567. Knowledge of El Greco’s years in Italy is limited.

He lived in Venice until 1570 and was a “disciple” of Titian, who was by then in his eighties but still vigorous. Unlike other Cretan artists who had moved to Venice, El Greco substantially altered his style and sought to distinguish himself by inventing new and unusual interpretations of traditional religious subject matter.[20] His works painted in Italy were influenced by the Venetian Renaissance style of the period, with agile, elongated figures reminiscent of Tintoretto and a chromatic framework that connects him to Titian. As a result of his stay in Rome, his works were enriched with elements such as violent perspective vanishing points or strange attitudes struck by the figures with their repeated twisting and turning and tempestuous gestures; all elements of Mannerism.

If Crete gave El Greco his descent and the heart of his art, if Italy gave him the style and the fundamental artistic preparation, Spain and Toledo allowed him to immerse himself in a religious environment full of Spanish mysticism. According to Hortensio Félix Paravicino, a 17th-century Spanish preacher and poet, “Crete gave him life and the painter’s craft, Toledo a better homeland, where through Death he began to achieve eternal life.”

Because of his unconventional artistic beliefs (such as his dismissal of Michelangelo’s technique) and personality, El Greco soon acquired enemies in Rome. In 1577, El Greco migrated to Madrid, then to Toledo, where he produced his mature works. At the time, Toledo was the religious capital of Spain and a populous city with “an illustrious past, a prosperous present and an uncertain future”. El Greco regarded colour as the most important and the most ungovernable element of painting, and declared that colour had primacy over form. In his mature works El Greco demonstrated a characteristic tendency to dramatise rather than to describe.The strong spiritual emotion transfers from painting directly to the audience.

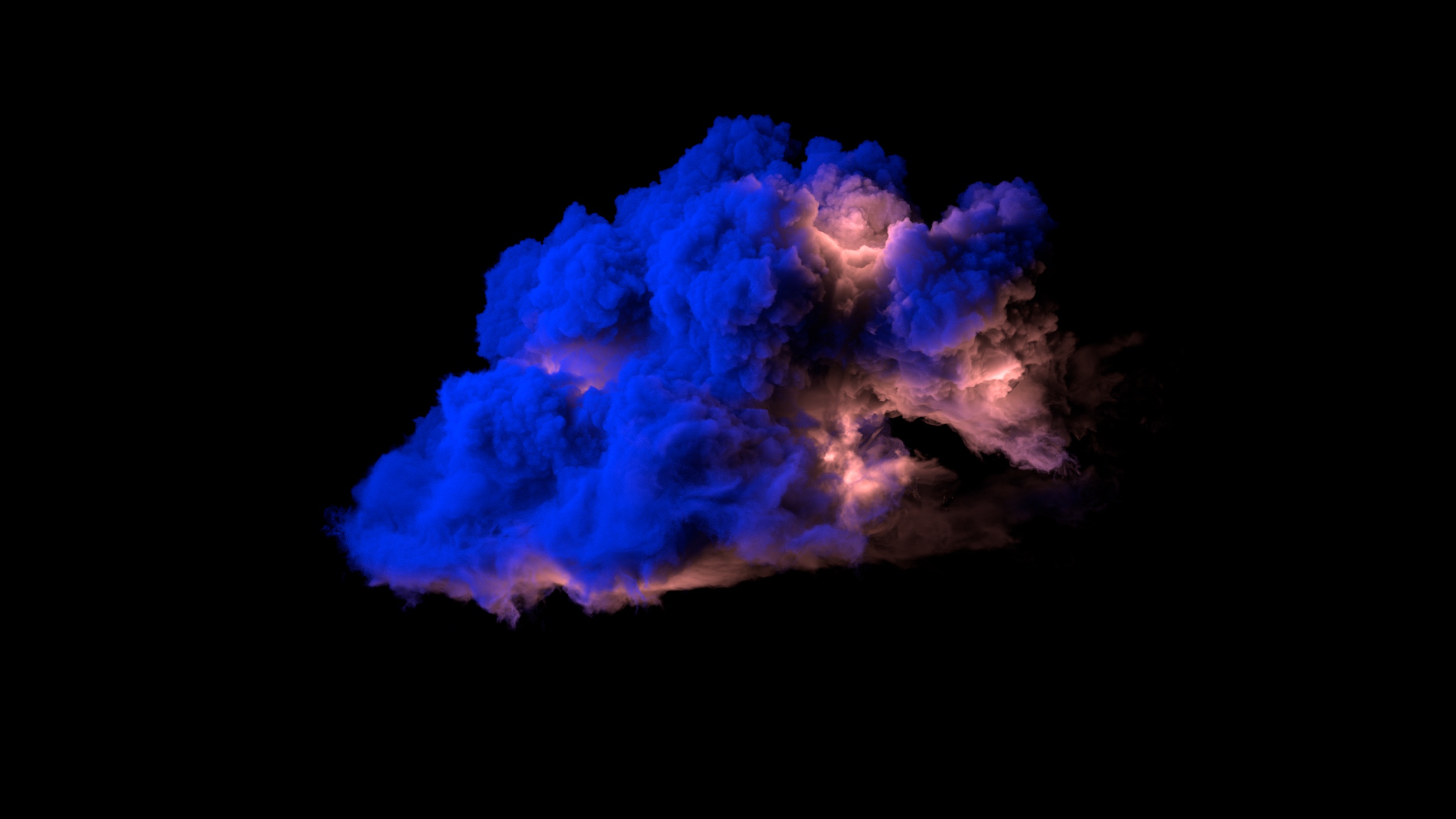

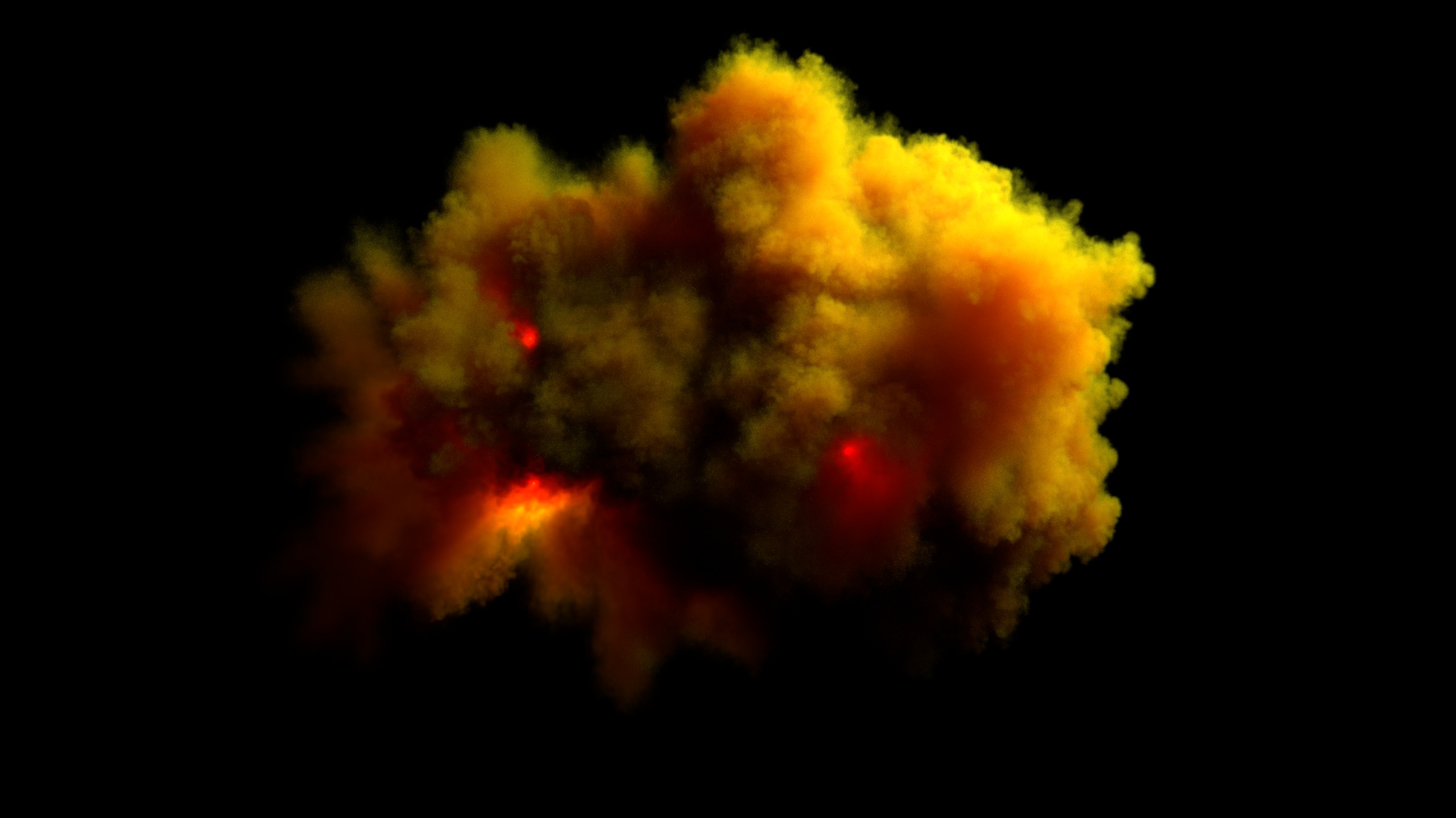

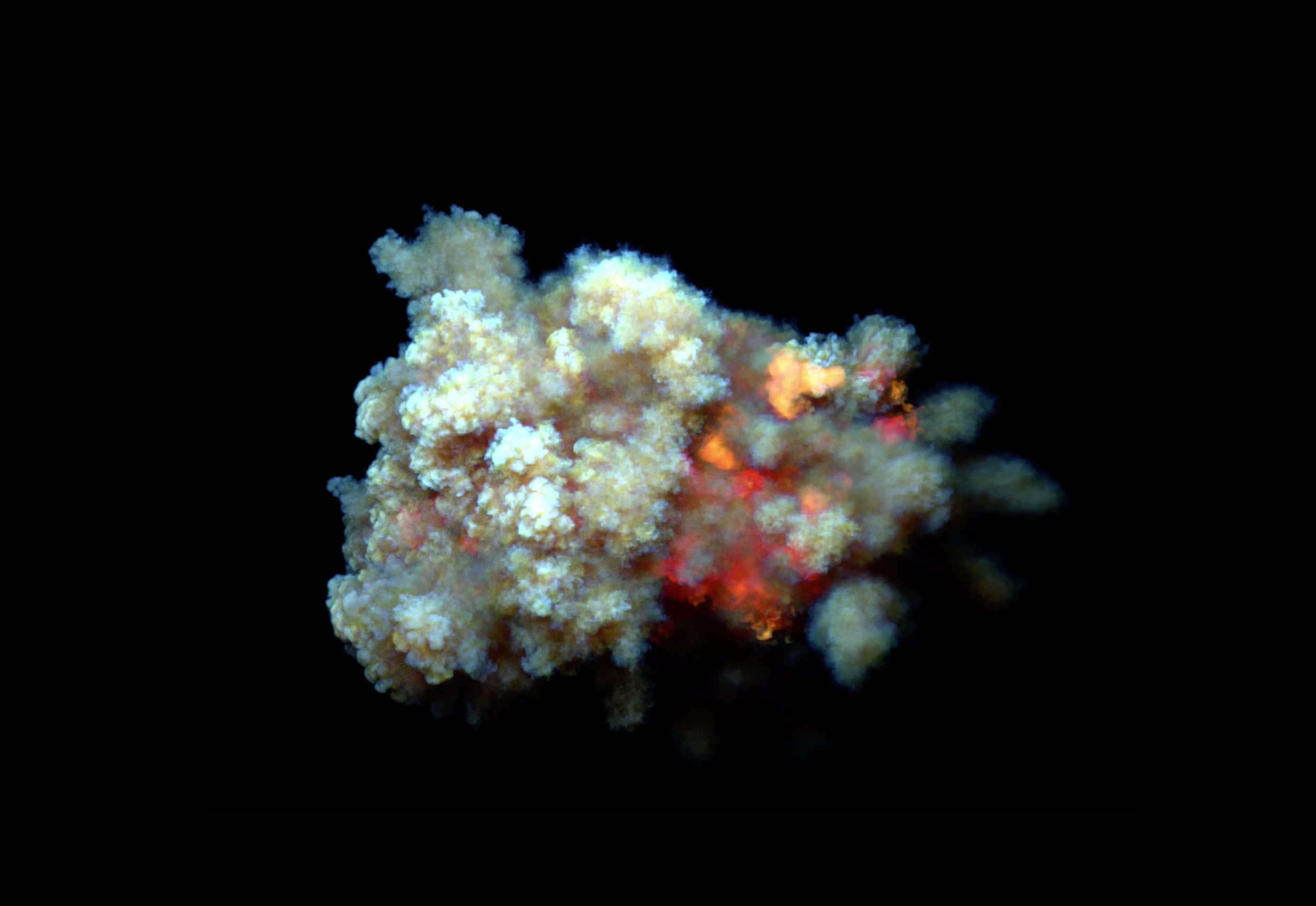

El Greco’s elongated figures seem to dissolve and mold with their surroundings. Everything is liquified, emerging into a light that shines from unknown sources, almost from inside the figures themselves. The festival’s visual language is the product of computer particle simulations, cloud-like formations, shapes both defined and undefined at the same time, lit from the outside but also from within themselves.